Racial Covenants in the Chicago History Museum Archives

By Hannah Simmons

Going through an archive is like embarking on a time-traveling expedition. Opening box after box and carefully fluttering through worn documents, you are greeted with an image of the past and a clearer understanding of present circumstances. Going through the archives in the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center is no different. The volume of sources the collection holds is breathtaking, and the image of racially restrictive covenants it paints is striking. For example, in the Abakanowicz Research Center’s collection on the Auburn Park Property Restriction Association, one finds the story of John Frederick Wagner.

Born in Chicago on August 28, 1878, to German immigrants, William Wagner and Mary Nachel, John Wagner went on to become a lawyer and marry Eleanor Siebert. By 1910, John and Eleanor Wagner lived in the then all-white, majority second-generation European immigrant neighborhood of Auburn Gresham on the far Southwest Side. From all accounts, John Wagner was an everyday individual. However, on August 9, 1929, he entered the archival records.

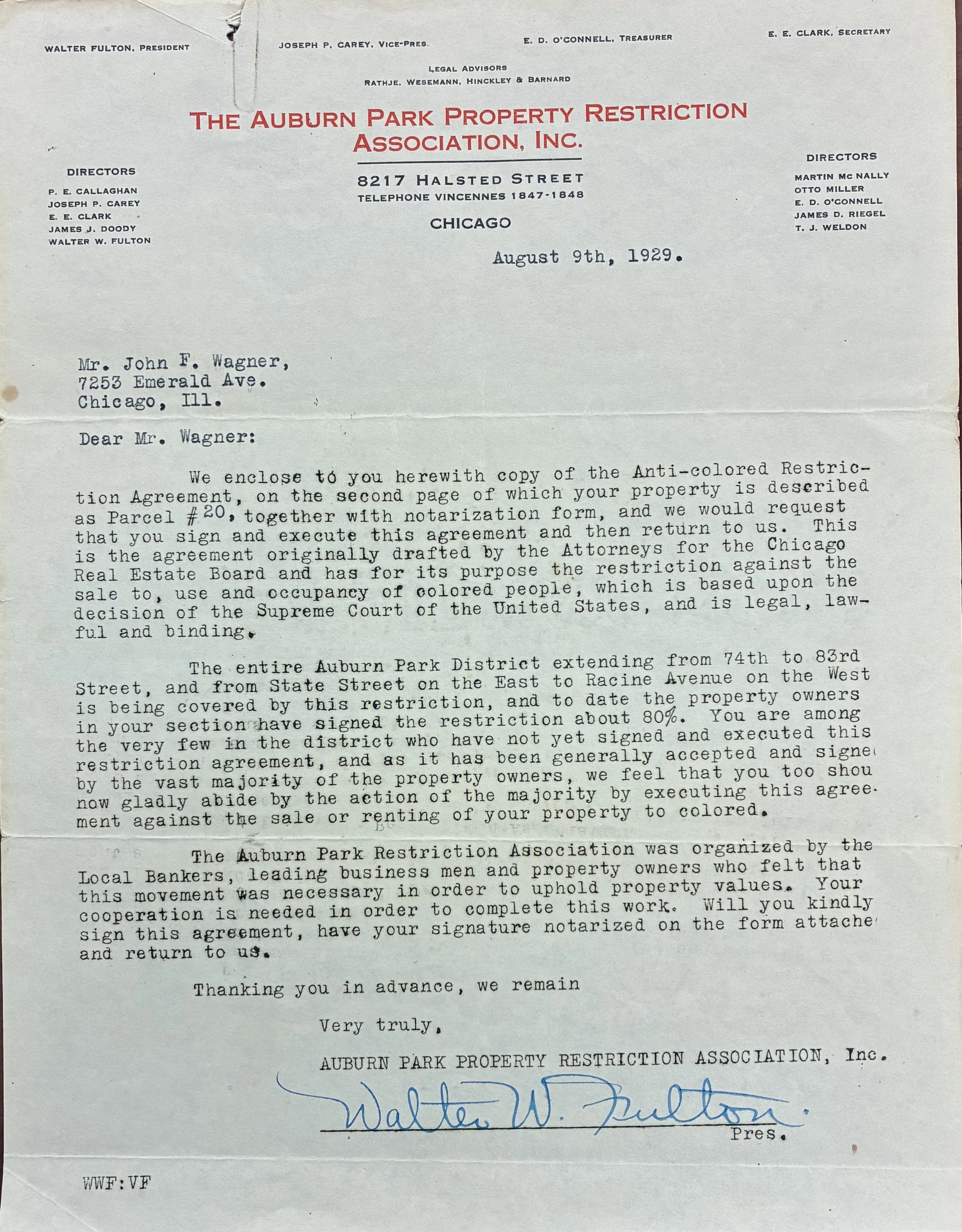

On August 9, 1929, Wagner, who had been living in Auburn Park for nearly two decades, received a letter from the Auburn Park Property Restriction Association. In the letter, the Restriction Association wrote, “the entire Auburn Park District extending from 74th to 83rd Street, and from State Street on the East to Racine Avenue on the West[,] being covered by this restriction, and to date, the property owners in your section have signed the restriction about 80%. You are among the very few in the district who have not yet signed and executed this restriction agreement, and as it has been generally accepted and signed by the vast majority of property owners, we feel that you too should now gladly abide by the action of the majority by executing this agreement against the sale or renting of your property to colored.” There is no indication why Wagner had not signed the covenant. However, two things are clear. First, most neighbors in Auburn Gresham had signed a racially restrictive covenant. Second, there was pressure on Wagner to do the same. Attached to the letter was a copy of an “anti-colored restriction agreement” for Wagner to sign. According to the agreement, the purpose of signing was to keep the neighborhood all white by prohibiting the sale of any property to all persons having “one-eighth part or more of negro blood.” Restriction agreements like the one Wagner received are a small part of the larger history of racially restrictive covenants in the Chicagoland area. The Abakanowicz Research Center has sources detailing this history.

Letter from Auburn Park Property Association to John Wagner, August 9, 1929.

The Abakanowicz Research Center has four known racially restrictive covenants, one from the Near North Side Property Owners’ Association to the Chicago Historical Society, asking the Society to sign a restrictive covenant, a letter from the Woodlawn Property Owners’ Association, thanking a property owner for their due payment that would help keep “Woodlawn to white people,” one from Auburn Park Property Restriction Association, and one in the Archibald J. Motley collection from the Englewood Property Restriction Association. While these are the known covenants, there are certainly more in the collection. For example, while going through the papers of the local real estate company, Baird and Warner, one finds mention of a building under covenant in Old Town. This mention of the building under covenant shows that while institutions and individual neighbors signed covenants, some of the main enforcers were real estate companies.

The boundaries of the Auburn Gresham (bottom left), Englewood (top left), and Woodlawn (top right) neighborhoods.

Real estate companies, like Baird and Warner, promoted covenants based on the idea that if Black people were allowed to buy property, property values would go down, the area would become blighted, and would eventually turn into a slum. In a pro-covenant paper simply titled Restrictive Covenants (July 1944), found in the Bowes Realty Collection, the Federation of Chicago Neighborhoods lamented how unjust it would be for white soldiers to come back from war to find that their “homes have been taken over by negroes” and their old neighborhoods were now slums (15). The paper made no mention of how Black soldiers would feel coming back to housing discrimination. However, continuing to comb through the archives, particularly the Catholic Interracial Council (CIC) archives, one sees that Black Chicagoans and their allies, like members of the CIC, did not simply accept racially restrictive covenants; they pushed back against covenants and the segregationist logic that covenants were entrenched in.

In an impassioned letter in the CIC records, a Chicago Servite missionary, and regular author for the Novena Notes column, Father Hugh Calkins, O.S.M., was credited with stating, “Let white families stay and live together like Christians with Negroes. Either you admit they are equals or you don’t. If you don’t, you profess Hitler’s doctrines, branded false by science, forbidden by the inspired word of God, condemned by the Pope.” This powerful condemnation of racial segregation shows that there was a severe problem with segregation in housing in Chicago, which covenants exacerbated. After years of people like Father Calkins decrying the unconstitutional, undemocratic, and immoral nature of covenants, in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the Supreme Court decided that racially restrictive housing covenants could not be enforced. This was a blow against covenant makers and enforcers and a win for those who pushed back against covenants. Whether through fervent writings like Calkins or through the African American-promoted Double-V campaign (victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home), one sees that people questioned and pushed back against the logic, morality, and legality of covenants.

Racial covenants were, and are, hidden in plain sight. These documents were so prevalent that we can find them throughout land and historical archives. While we can see that these quotidian, legal instruments shaped housing in Chicago, we can also see how Black Chicagoans, and their allies, attempted to reshape housing in Chicago, attempting to unravel the harm covenants caused. Discussing the prevalence and pushback against racial covenants is crucial, and the archive makes it possible to tell both sides of the story.

Hannah Simmons is a 2025-2026 Black Metropolis Graduate Assistant, working with the Chicago History Museum and the Chicago Covenants Project.

Chatham, The Soul Queen, and Covenants: A Conversation with Cristen Brown

Throughout the early twentieth century, racially restrictive covenants confined Chicago’s Black residents to the city’s crowded “Black Belt.” In her recent article for South Side Weekly, “Best Former House of Royalty: Mid-Century Modern Home of Soul Queen Helen C. Maybell Anglin,” Cristen Brown illustrates how the dismantling of these race-based covenants created new opportunities for Black homeownership and fostered architectural innovation in the South Side neighborhood of Chatham.

In this conversation, Cristen Brown reflects on what inspired her to tell Chatham’s story, how the Chicago Covenants Project deepened her understanding of the neighborhood’s past, and why she hopes readers will see the city and its buildings with renewed curiosity and care.

Helen C. Maybell Anglin poses in front of her Chatham home, 1974. (Source: Perry C. Riddle, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum)

What drew you to write about the Chatham neighborhood?

“I'm a huge building nerd. I spend a lot of time photographing, researching and talking about buildings. I especially love exuberant, creative architecture, and Chatham is full of it. But more than that, Chatham is a neighborhood where every block seems to pulse with history and every building has a story to tell. These stories are layered into the built environment, and sometimes your clue about where to go digging is an architectural style that stands out for one reason or another. In Chatham, these mid-century modern homes are strikingly different from anything else in the neighborhood, and I had to know more. What I found when I started researching was so incredible that I needed to share it.”

How did the Chicago Covenants Project inform or deepen your understanding of the neighborhood’s history?

“As a Black Chicagoan, the work of the Chicago Covenants Project is not abstract. It helps to flesh out my own family’s history in this city. Whether they were moving to Chicago from the West Indies or the deep south, all branches of my family ended up living in the “Black Belt,” confined there by a mix of codified racism in the form of redlining and/or racially restrictive covenants. My great-grandfather couldn’t even bury his wife in the closest cemetery because of discriminatory practices that restricted where Black people could be laid to rest. So there’s definitely an anecdotal understanding of how this worked in our city.

The Chicago Covenants Project, however, gives us the hard data needed to understand broader patterns of how racially restrictive covenants were deployed across Chicago, which in turn gives us greater context for Black movement throughout the city–or the lack thereof. It’s not until the covenants were ruled unenforceable in 1948 that you begin to see us slowly move into other neighborhoods. First those directly adjacent to the ‘Black Belt,’ and later those a little farther south, like Chatham. Having the details on this is imperative to understanding why Black professionals showed up in Chatham just a handful of years after that 1948 decision, and is also helpful in terms of extrapolating why they may have ended up in that neighborhood specifically.”

What do you hope readers take away from this story?

“I am fascinated by the way Chicagoans express themselves through the built environment, from the most famous skyscrapers downtown to modest homes in our farthest flung neighborhoods. Every building tells a story, and I want people to look around their neighborhoods and find the stories. I want them to recognize and celebrate the beauty that surrounds them, even when no one else does. I want them to find the stories that explain the past and inform the future, and I want them to share what they discover so that we can learn too.”

Read Brown’s article “Best Former House of Royalty: Mid-century modern home of ‘Soul Queen’ Helen C. Maybell Anglin — Chatham” in South Side Weekly.

Cristen Brown photographing Chicago-area architecture. (Source: author provided)

Al Capone’s Covenant

By Ben Miller

In the late 1920s, covenant fever swept the South Side of Chicago. As the city’s Black population boomed, white residents mobilized to prevent their neighborhoods from becoming integrated. Realtors, businesses, and community groups worked to convince homeowners to sign agreements that barred Black families from ever buying or renting their properties. In Park Manor, nine miles south of the Loop, covenant organizers conscripted a surprising ally: the city’s most infamous gangster, Al Capone.

When he was not hiding from police or his gangland rivals, Capone lived at 7244 Prairie Ave, a modest home in the heart of Park Manor. Capone’s neighbors included a mix of longtime Irish and German residents alongside first-generation Americans like himself (mostly from Italy and Sweden). Park Manorites had no common nationality, but they shared a commitment to keeping their neighborhood racially homogenous. Like most white Chicagoans at the time, they believed that people of different races could not live peacefully together and that any rupture in the color line would cause chaos and devastate property values. In 1927, the Park Manor Improvement Association dedicated itself to excluding Black people by covering the entire neighborhood with racial covenants. To pull it off, the association needed signatures from every property owner they could find, including the denizen of 7244 Prairie Ave.

Capone’s house at 7244 Prairie Ave, as it appeared in 1929. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Park Manor residents knew perfectly well who owned the home—and not just because of the bomb-proof steel bars that guarded its windows. Capone openly listed himself as the resident of 7244 Prairie Ave in Chicago’s 1923 telephone directory. The following year, the house hosted dozens of mobsters for a lavish funeral after Capone’s brother Frank died in a shootout. Chicago police even besieged the property around Christmas in 1927, part of an effort to harass Capone into leaving town.

In fact, covenant organizers turned their attention to the 7200 block of Prairie Ave just weeks after Capone’s most infamous act: the St. Valentine’s Day massacre that killed seven of his North Side enemies on February 14, 1929. The crime made international headlines, but it did not change the calculus for the proponents of race restriction. To prevent Black migration into Park Manor, covenants needed to cover as many houses as possible. What the owners of those properties did professionally didn’t seem relevant.

On May 25, 1929, organizers arrived to collect a signature for 7244 Prairie Ave. Capone had just been jailed on a gun charge in Pennsylvania, but his mother Theresa was available to sign since the property was officially titled under her name. Theresa dutifully added the Capone home to a covenant which proclaimed that “no part of said premises shall in any manner be used or occupied directly or indirectly by any negro or negroes.” A notary public then certified her signature as real and freely given. A week later, organizers filed the covenant with the Cook County Recorder of Deeds, making it legally binding.

Theresa Capone signed the covenant twice to cover both lots that formed the Capone homestead at 7244 Prairie Ave. Below, notary William Tyler affirmed that her signature was valid.

Black Chicagoans didn’t miss the irony. An editorial in the Defender remarked bitterly that the same neighborhoods which used covenants to exclude African Americans imposed “no penalty upon white criminality.” Capone and other gangsters like Dean O’Banion lived in respectable white communities whose residents left them alone. Meanwhile, law-abiding Black citizens faced vicious discrimination “not because they are criminals or indulge in activities which bring their city and community into disrepute, but because of their racial connections.” African Americans, the paper noted, were treated like “any far-seeing social group would treat its criminals.”

Absurd as it was, the Capone family’s presence on a covenant encapsulated how white Chicagoans understood their homes and communities in the 1920s. Capone may have been a murderous bootlegger, but his criminal empire did not threaten the dreams or pocketbooks of ordinary families. Desegregation, on the other hand, loomed menacingly in a world where most white people saw race mixing as synonymous with violence and decline. This sort of racial logic survived much longer than the Park Manor covenant itself, helping sustain Chicago as one of the most segregated cities in America.

Sources:

“Another Reason for Crime,” Chicago Defender, July 7, 1928.

“Capone, Echoed by Saltis, Cries Out Desperation,” Chicago Tribune, December 27, 1927.

Document 103877098, Book 27311, Page 50-51.

Wallace Best, “Greater Grand Crossing” in Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/547.html.

Tom Philpott, The Slum and the Ghetto, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 198-199.

Maintaining Clear Title Through Disaster

By Maura Fennelly

Nearly 3,500 property index books containing millions of property transactions sit in the basement of Cook County Clerk’s “Tract Department” where our biweekly research sessions take place. As our team of volunteers attentively comb through books to locate covenants, Cook County residents come down to speak with Tracts staff about the “chain of title” on their or their loved ones’ properties. Meanwhile, several title search employees work their way through index books and computer searches to create an abstract of title, which is necessary for getting title insurance that guarantees legal ownership of land. Why are covenant and title researchers working in the same space and interacting with the same analog county property records?

While there are some minor variations to how the 3,141 U.S. counties store property records in their “registries”, the overall system “is remarkably uniform across the country”, according to legal scholar K-Sue Park. Some county registries are digital, some are analog, and some, like Cook, are a mix of both. The purpose of registries is also uniform: to determine who legally owns a parcel of land. Index books note who the originator (grantor) and receiver (grantee) are for every transaction ranging from mortgage creations to racially restrictive covenants [1]. In his dissertation on the Chicago Real Estate Board, sociologist Everett Hughes found that real estate stakeholders need titles to be “secure and easily transferable. This condition depends on complete and accessible records”. Without the records, title companies cannot provide title insurance that provides protection against any unsettled defects [2].

The Cook County Clerk follows a similar system of tracking property transactions like other counties, but is unique in how it maintained its records through disaster. Without the forward thinking of private title companies, the County would have lost all property documentation spanning back to 1819 when Illinois established county recorders. Lawyer Edward Rucker came up with an efficient system to note property transactions more efficiently and joined forces with real estate developer James Rees to create the first title abstract business in the city. Three brothers joined Rucker and Reese to create Chase Brothers & Co., which along with Shorall & Hoard and Jones & Seller were the three main title abstract companies in Chicago that formed during the mid 1800s as real estate boomed and speculators desired clear ownership.

The location of the City-County building is covered by the red “burnt district” in the loop. While the building our research sessions are in was built in 1911, the location has been the same since 1853. (Source: Newberry Library, Chicago and the Midwest)

Yet clear ownership and legal protections were suddenly upended by The Great Chicago Fire. The 1871 fire destroyed almost all of the County’s real estate records as City Hall burned. The Chicago Times reported: “There has been absolute destruction of all legal evidence of titles to property in Cook County. The annoyance, calamity and actual distress that will arise from this misfortune are not yet properly appreciated. Something equal to the necessities of the case must be done quickly.”

Chicago City Hall 1871 pre- and post-fire (taken 5 days apart). (Source: Chicago History Museum, Prints and Photographs Collection)

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, there was uncertainty over how the rights to ownership would be upheld. Legal scholar and member of Chicago Title & Trust Company Walter Smith wrote in 1928, “As the destruction of the book containing the record does not destroy the legal effect of the record, every purchaser is charged by law with notice of what was contained in these burned volumes. As our Supreme Court said in a case concerning the destruction of the records, ‘The situation of owners of property in Chicago was appalling”’ [3]. The three title firms miraculously had their own copies of the property records, along with index books and abstracts of property transactions. For example, Lyman Baird’s real estate firm had a fireproof safe that kept the records in one piece.

Instead of using the moment of disaster to increase transaction costs from property owners, the three title firms pieced together their respective records. Walter Smith argues that “by combining their salvage they would have a complete set of all the necessary books, with some duplications, as well as letter press copies of a large number of abstracts theretofore made”. Yet the records alone didn’t guarantee legal title. Thanks to the three title firms’ willingness to reestablish accurate record-keeping, the Illinois legislature was able to pass the Burnt Records Act in 1872 (today it is known as the Destroyed Public Records Act), which meant that courts could use private companies’ property records to determine title ownership of properties.

An example of a title insurance policy from Title Guarantee and Trust Company.

Without the collaboration between the state, title companies, and real estate industry to address the lack of documentation over “who owned what”, property owners across the city would have had to deal with extensive and costly legal battles. Instead, developers immediately began to rebuild the city and heeded the call from Chicago Tribune co-owner William Bross that “the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN.” Professor Carl Smith highlights how developers effectively rebuilt the downtown within two years, although fireproofing building codes didn’t go into effect until after a second smaller fire in 1874.

Perhaps influenced by the fire’s destruction, the Illinois legislature was the “first state to pass title registration law” called the “Torrens Title Act” in 1897. Real estate stakeholders embraced the new act because there would be a clearer record of who or what entity was the legal owner of the land so mortgages could be guaranteed. The Chicago Real Estate Board was a strong support of land title reform to speed up real estate transactions and:

“It advocates control of the use of land , as a means of giving to real estate values that stability and predictability which will enable the purchaser to know what he is buying. Not stability in itself, but in relation to investment and the market concerns the real estate agent. The Realtor is continually preparing land for the market, and is interested in whatever measures seem to facilitate its, marketability” (Hughes 1931, 85).

Just as the Board was advocating for racial covenants as a tool for stability in valuation, it also wanted title reform to create expectations that property would be protected through legal means [4]. Land titles continue to offer owners confidence in property ownership; racial covenants offered White owners a sense of assurance in property values. Both mechanisms focus on ownership as the legal right to exclude others from a parcel, or parcels, of land. There is much to be discovered within the nation’s property registries in terms of their idiosyncratic histories and “how registries themselves have been the site of struggles to determine who can own property and what ownership means” (Park).

Notes

In Cook County, covenant entries’ grantors read “[last name] et al.” and the grantee is blank because the agreement was between neighbors and not just between owners of one parcel.

Cook County uses both the Torrens system and the traditional title insurance method. The Torrens system originated in Australia and was most common in the County until the 1930s. Read more here.

Park notes that other county records have been entirely destroyed due to natural disasters or arson during the Civil war.

The Chicago Real Estate Board was fundamental in establishing and spreading racial covenants. The board instructed its members to establish property restriction associations so White owners would be deterred from selling to Black people. The board would expel realtors who did not obey.

Works Cited

https://www.ilsos.gov/departments/archives/IRAD/recorder.html

https://www.newberry.org/blog/the-house-that-survived-the-great-chicago-fire

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1262.html

https://www.ctic.com/history2.aspx

http://images.chicagohistory.org/asset/4335/

https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1167&context=cklawreview

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x002089360

https://www.chipublib.org/fa-horace-g-chase-papers/

The Story of Frederick H. Bartlett

By Raj Aggarwal

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Bartlett was born into an era of rapid industrialization and urban expansion. At age 15, he moved from New York to Texas to Chicago, where he established himself in 1890. Like many young men in search of economic opportunity, Bartlett began working in retail, starting as a stock boy for the Marshall Field & Co. department store. His early years at Marshall Field's allowed him to gain experience in sales and business, eventually working his way up to a salesman position by 1896. This role provided him with skills in negotiation, customer relations, and financial sharpness, skills that would later prove invaluable in his real estate ventures.

In 1902, Bartlett took his first documented step into real estate, acquiring property in Chicago on Champlain Avenue that was 300 feet north of 43rd Street. This was located in Bronzeville, Chicago. This was located in the heart of Bronzeville, which would later be known as the "Black Metropolis," a major site for African Americans during the Great Migration. He formally launched his real estate career in 1904 by co-founding the firm Watson and Bartlett, which soon became Frederick H. Bartlett & Co. This firm would be his primary vehicle for real estate development, and he claimed it was the largest real estate firm in Chicago for more than three decades. As his business grew, so did his reputation, wealth, and influence.

Image of Frederick H. Bartlett (seated at the center of the table) with business associates, featured in a magazine where Bartlett wrote advice on finding success in sales

Real Estate Career and Development Strategies

Bartlett made a name for himself as a prominent figure in Chicago’s booming real estate market. By 1905, his success was evident in his luxurious lifestyle, including membership in an “autoist” club, an exclusive association for car enthusiasts. His prominence continued to grow, leading him to acquire substantial properties across Chicago. He later became a member of the Chicago Stock Exchange in 1927.

During the early 1900s, Bartlett’s career accompanied the rise of racially restrictive covenants in Chicago. These covenants were legally binding contracts that banned the sale of homes to certain racial, ethnic, or religious groups, most prominently targeting African Americans. During the early 1900s, coordinated campaigns conducted by realtors, neighborhood organizations, and professional real estate organizations established restrictive covenants throughout American cities. Chicago was no exception. Following the start of the First Great Migration in the 1910s and the subsequent Chicago Race Riot of 1919, many white people across the city held fears that racial integration was harmful, or even dangerous. From this anxiety, restrictive covenants would become an established practice that helped formalize residential segregation. This practice also came from realtors falsely believing that racially integrated housing lowered property values. Among many issues, the most direct would be African Americans being forced to live in places like Chicago's Black Belt. This would be an area where housing would be overcrowded and lead to deterioration, due to segregation and poverty.

An example of the sort of housing that African Americans had in Chicago

In this respect, Bartlett would be little different from the other leading realtors of his time, as he would help cement restrictive covenants into the city. Racially restrictive covenants in Chicago enforced segregation through two main tools: plat restrictions and agreement covenants. Plat restrictions were Bartlett’s tool of choice, exclusionary clauses written into subdivision plans by developers such as Bartlett, barring non-Caucasians from buying property and setting racial boundaries from the outset. Agreement covenants were private contracts among homeowners in already built-up areas to collectively refuse sales or rentals to certain groups, relying on community enforcement.

[Example of Bartlett race restrictions at #4 on the plat for Higgins Road Farms.]

One example of Bartlett’s use of plat restrictions would be in Roseland, a Chicago neighborhood near Lake Calumet. Between 1914 and 1918, Bartlett acquired over 3,000 lots in the Roseland area, where he implemented these restrictions to prevent African Americans and other minority groups from purchasing homes. Bartlett’s policies contributed significantly to the racial segregation of Chicago’s neighborhoods, a legacy that has continued to affect the city's demographic divisions for generations.

Before developing restrictive covenants in places like Roseland, Bartlett also embarked on a separate project in Lilydale, a substandard housing development intended specifically for African Americans. Despite claims in advertisements placed in the Black newspaper The Chicago Defender claiming that Lilydale offered high-quality housing, the development was below the standards of his other projects. The substandard nature of housing in Lilydale contrasted sharply with his more lucrative developments in white-only neighborhoods, underscoring the disparities in housing opportunities available to different racial groups in Chicago at the time.

Cover of an article in The Chicago Defender claiming that Lilydale was a prosperous new neighborhood developed by Bartlett & Co.

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Bartlett’s real estate firm thrived. He used various financial tactics to expand his influence, including acquiring property in prominent areas such as Hyde Park in 1916. His success was partially due to his strategic approach during World War I, a period in which housing demand grew significantly as workers flocked to cities like Chicago to meet wartime production needs. However, Bartlett’s business suffered during the Great Depression, prompting him to pause property acquisitions from 1926 until 1934. During this time, economic hardship forced many developers to scale back, but Bartlett was optimistic about the market's recovery under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies. He resumed his purchases in 1934, citing improvements brought by Roosevelt’s Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), which had stabilized the real estate market.

Later Life and Legacy

Bartlett’s influence in Chicago’s real estate market was well established by the late 1930s. He led a life of wealth and luxury, evident in his frequent participation in high-stakes leisure activities, such as a celebrated $25,000 golf game in 1937. Later in his life, he would retire in San Marino, California, living in a massive mansion until his death.

Image of Bartlett (man on the right) with one of his company’s managers

Despite his financial successes, Bartlett's career left a complex legacy. Bartlett would enjoy a luxurious life for his time, with that wealth being built, in large part, from racist housing practices. While he contributed to the economic growth of Chicago through extensive residential development, the neighborhoods he built were heavily segregated.

Conclusion

Frederick H. Bartlett’s life and career reflect the dynamics of early 20th-century American urban development and the social norms that accompanied it. His ascent from stock boy to prominent real estate developer demonstrates a remarkable journey shaped by ambition and business talent, as well as racial bigotry. His use of restrictive covenants and the substandard housing in Lilydale underscore the racial prejudices that he possessed and that were widespread in housing policies of his time. Bartlett’s influence on Chicago’s real estate market left a lasting impact on the city’s physical and social landscape, one that continues to resonate in discussions about housing equity and segregation today.

The Neglect of Restrictive Covenants in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series

By Raaj Aggarwal

Jacob Lawrence's powerful Migration Series is housed in two of America's premier art institutions—the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. His vibrant paintings captured the hopes and struggles of African Americans who left the rural South for cities in the North between 1910s and 1970s, seeking better economic opportunities and escaping racial violence. The migration started with hundreds of African Americans moving to the North, eventually culminating to six million migrating from the South to the North and West. Among the millions seeking a new leaf were Jacob Lawrence’s parents, who moved from the rural South to New Jersey, subsequently influencing Lawrence's Migration Series.

These paintings would depict the issues and dreams African Americans experienced in the South, as well as what migrants found in the North. With regards to the problems African Americans faced in the South, Lawrence did not shy away from highlighting the structural racism plaguing everyday society. An example can be seen in panel 22 (Figure 1), where African Americans in the South were put in shackles for, as Lawrence put it, “the slightest provocation.” However, a strange absence of structural racism could be found in how Lawrence depicted housing issues in the North. Lawrence showcased the cramped nature of migrants’ housing in the North in panel 48 (Figure 2), portraying tightly packed beds in single rooms with little living space. Yet within this panel, there’s no sense of where these housing issues came from. One could guess that the police were the ones putting African Americans in shackles in the South. However, Lawrence’s depiction of housing issues in the North makes it unclear as to where they came from. While panel 48 provides the sense that there was no culprit for poor housing, the reality was much grimmer. As migrants came out of the rural south searching for respite from an onslaught of racism, they would encounter a complex web of white supremacy that forced them into the sort of housing Lawrence portrays.

Figure 1: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 22. “Migrants left. They did not feel safe. It was not wise to be found on the streets late at night. They were arrested on the slightest provocation.” Tempera on Masonite, 12" x 18". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Figure 2: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 48. “Housing was a serious problem.” Tempera on Masonite, 18" x 12". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was a renowned African American painter and educator whose work profoundly influenced American art. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence would eventually move to Harlem with his family during his youth. This experience deeply impacted Lawrence and helped lead to his art career, leading to the creation of The Migration Series. These paintings, created between 1940 and 1941, consists of sixty panels depicting the nationwide journey of African Americans from the South to the North. They brilliantly capture the struggles, hopes, and resilience of those seeking better lives. As such, the Migration Series remains a significant work in American art history, celebrated for its powerful narrative, artistic innovation, and masterful portrayal of the African Americans experience.

While Lawrence’s work captured the challenges to housing for Black migrants, his work lacked a display of restrictive covenants that explained these challenges. These covenants were legal agreements that prohibited the sale of homes to certain racial, ethnic, or religious groups, most commonly targeting African Americans. Emerging in the early 20th century, these covenants had numerous negative effects for African Americans, such as worsening the quality of housing for Black migrants. Yet throughout Lawrence’s artwork on the housing challenges African Americans faced in the North, there was no portrayal of restrictive covenants.

This lack of residential segregation can be seen in several panels showcasing poor housing African Americans had while lacking explanation for these hardships. Lawrence portrayed that housing was better in the North compared to the South in panel 31 (Figure 3) and panel 44 (Figure 4). However, Lawrence also portrayed Northern housing to be overcrowded and run down in panels 47 (Figure 5) and 48 (Figure 2). The makeshift bed in panel 47 and lack of living space in panel 48 creates a sense that Black migrants’ lives were far from perfect. Yet these portrayals don’t show that these issues came in part from structural racism and racial prejudice.

Figure 3: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 31. “The migrants found improved housing when they arrived north.” Tempera on Masonite, 12" x 18". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Figure 4: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 44. “But living conditions were better in the North.” Tempera on Masonite, 12" x 18". (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Figure 5: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 47. “As the migrant population grew, good housing became scarce. Workers were forced to live in overcrowded and dilapidated tenement houses.” Tempera on Masonite, 18" x 12". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

The narrative the Migration Series portrays is that African Americans simply found themselves in lackluster housing, as opposed to being confined by an extensive system of bigotry. Yet in the case of restrictive covenants, a lack of bigotry wasn’t the situation. Historian Wendy Plotkin documents the prejudice found in Newton Farr, the president of the National Association of Real Estate Boards and Chicago Real Estate Board starting in the early 1930s. Plotkin writes that, “In an extraordinary interview with the Chicago Defender, in early 1945, Newton asserted

‘Restrictive covenants are made to keep out undesirable people. Negroes are undesirable. . . . Negroes enjoy sex too much. Inclined to be promiscuous. Are mostly uneducated. The majority of them are poor-ragged-dirty. They're underfed.’”

While the interview was a few years after Lawrence’s Migration Series, Farr’s prejudice likely existed well before 1941.

Although Lawrence did not depict racism being connected to housing issues, Lawrence did illustrate racial violence in the North. One example is in panel 50 (Figure 6), which depicts a white man with extreme hatred in his violent act. The spiked fingers on the white man’s hand and intensity of his facial expression makes clear his intent. Resentment towards migrants is further shown in panel 51 (Figure 7), showcasing white mobs viciously bombing the homes of African American newcomers. As such, when Lawrence’s portrayal of housing in the North is contrasted with his depiction of racial violence, one could get a sense that Northern racism only involved racial violence without any structural forms.

Figure 6: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 44. “Race riots were numerous. White workers were hostile toward the migrant who had been hired to break strikes.” Tempera on Masonite, 18" x 12". (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Figure 7: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 51. “African Americans seeking to find better housing attempted to move into new areas. This resulted in the bombing of their new homes.” Tempera on Masonite, 18" x 12". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

The psychological scarring caused by restrictive covenants and other forms of racism in the North was captured by other African American artists at the time. Richard Wright’s 1940 novel Native Son powerfully illustrates the impact African Americans felt in response to issues like the racial violence Lawrence portrayed. Wright illustrates how the main character of his novel, a black man named Bigger living in Chicago, felt the need to act submissively to Mr. Dalton, a white man whom Biggie seeks to work for:

"Bigger had not raised his eyes to the level of Mr. Dalton's face once since he had been in the house. He stood with his knees slightly bent, his lips partly open, his shoulders stooped; and his eyes held a look that went only to the surface of things. There was an organic conviction in him that this was the way white folks wanted him to be when in their presence; none had ever told him that in so many words, but their manner had made him feel that they did."

Bigger would later discover that Mr. Dalton was responsible for trapping Black Chicagoans in the oppressive conditions of ghetto housing through his control of real estate. Langston Hughes more directly explored residential segregation in his 1949 poem titled “Restrictive Covenants.” In it, he examines how African Americans were both psychologically and physically deprived of freedom:

“When I move

Into a neighborhood

Folks fly.

Even every foreigner

That can move, moves.

Why?

The moon doesn’t run.

Neither does the sun.

In Chicago

They’ve got covenants

Restricting me—

Hemmed in

On the South Side,

Can’t breathe free.

But the wind blows there.

I reckon the wind

Must care.”

The portrayals of northern racism in the 1940s from Lawrence, Wright, and Hughes show the different ways African American artists grappled with depicting white supremacy, each with varying degrees of illustrating residential segregation.

The Migration Series’s absence of covenants is further problematic when the portrayal of Southern discrimination is contrasted with the North, since the panels focusing on the South depicted structural racism. One example can be seen in panel 14 (Figure 8), depicting African Americans as having no justice in Southern courts. In this painting, Lawrence portrayed African Americans in the South to be powerless against overwhelming systemic injustice, as evidenced by the white judge towering over the African Americans. As such, Lawrence’s depiction of Northern prejudice creates a narrative that systemic racism was only found in the South.

Figure 8: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 14. “For African Americans there was no justice in southern courts.” Tempera on Masonite, 18" x 12". (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

It is possible that Lawrence in 1940 did not know about restrictive covenants or had heard of these contracts but had no sense of their widespread support and effects. Regardless of this omission, it doesn’t change the fact that Lawrence’s Migration Series remains one of the most powerful, impressive portrayals of the Great Migration. It’s also important to note that while African Americans certainly faced challenges in the North, migrants would also have better lives in many respects, such as Lawrence portraying better educational opportunities in panel 58 and the freedom to vote in panel 59. Yet with this considered, the reasons for the poor housing Lawrence depicted must be remembered. African Americans did not simply stumble across deficient homes. Instead, migrants escaped a world of unimaginable abuse only to be welcomed by a new system of ruthless oppression that confined them inside the ghetto.

References

Plotkin, Wendy. “Plotkin, "Deeds of Mistrust: Race, Housing, and Restrictive Covenants in Chicago: 1900-1953,” PhD Diss. University of Illinois, 1999.

Analyzing the Relationship Between the Great Migration and Racially Restrictive Covenants

By Raaj Aggarwal

Set in the South during the early 1900s, panel 33 of Jacob Lawrence’s 1941 Migration Series conveys two emotions. On the left, the painting depicts an African American child kneeling down with their hands on their face, perhaps sobbing, listening to their mother read a letter, or being in deep contemplation. Nevertheless, the figure seems to convey a sense of defeat. In the middle of the painting showcases another African American with a letter in her hand. Her expression seemingly conveys both a sense of defeat for life in the South and a longing for what hope could be found in the North, the letter offering an escape from misery. The caption for this painting reads, “People who had not yet come North received letters from their relatives telling them of the better conditions that existed in the North.” As such, Lawrence’s 1941 painting gives the impression of both a sense of loss and defeat from the South’s daily grind, and a sense of hope of what could be discovered in the north. In the words of art historian Jodi Roberts commenting on this painting, the letters sent to the South, “Stoked hopes of escaping the drudgery and poverty that many black Southerners endured.” This painting depicts the sentiments of African Americans during the First Great Migration, the period from 1910-1940 that featured millions of African Americans escaping the brutalities of the Jim Crow South with the hopes of finding better life in the North. When considering the common thread within the lives of African American migrants, Isabel Wilkerson in The Warmth of Other Suns wrote that, "What binds these stories together was the back-against-the-wall, reluctant yet hopeful search for something better, any place but where they were." Yet even with these hopes for improved life, migrants would be welcomed by a new form of racial discrimination known as racially restrictive covenants, which was reminiscent of the segregation found in the rural South. Chicago was no exception, with Timuel Black in Bridges of Memory: Chicago's First Wave of Black Migration writing that The Windy City was, "A city of restrictive covenants, of official brutishness, of less than benign neglect. Yet, with miraculous stubborness, [migrants] 'got over.'"

Figure 1: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41. Panel 33. “People who had not yet come North received letters from their relatives telling them of the better conditions that existed in the North.” Tempera on Masonite, 12" x 18". (The Philips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

During the Great Migration, African Americans were driven to migrate by a wide variety of factors, such as the harsh realities of Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the South, as well as the widespread violence and economic disadvantage faced by Black communities. These experiences were vividly captured in the 1940 song “Times is Gettin’ Harder'' by Southern Blues singer and guitarist Lucious Curtis:

Times is gettin' harder,

Money’s gettin' scarce.

Soon as I gather my cotton and corn,

I’m bound to leave this place.

White folks sittin' in the parlor,

Eatin' that cake and cream,

N—–’s way down to the kitchen,

Squabblin' over turnip greens.”

In addition to the “push” factors of hardship in the South, there were also “pull” factors that motivated migrants to make the trek North. The promise of better jobs, higher wages, and improved living conditions, along with the chance for greater political and social freedoms, drew many African Americans to leave the South in search of a better life. Chicago was no exception, as a 1922 survey of black migrants found that African Americans came to The Windy City in search for better ways to support their family and improved living conditions. All of these factors coalesced into a hope of finding better life when compared to the merciless life of the South.

Family of African Americans migrating out of the South. Library of Congress

Some of these dreams were realized while others were stunted, as Isabel Wilkerson writes that for African American migrants, "The New World held out higher wages but staggering rents that the people had to calculate like a foreign currency."

While many migrants were able to find better jobs in Chicago, inferior living standards and rampant racism would still be present in many domains of life, including housing. In Chicago and many other cities across the country, a chief instrument of housing segregation in the first half of the 20th century came in the form of racially restrictive covenants. These were legally enforceable deeds signed by property owners that restricted certain races, such as African Americans, from occupying covenanted housing. The detrimental effects of restrictive covenants were numerous, such as forcing African Americans into dilapidated and overcrowded housing and creating racially segregated schools within covenanted areas. As such, much of the tenement housing in Bronzeville would be converted into one room kitchenettes. Timuel Black recalls in his experience living in Chicago that, "Our family lived in a nice, large apartment, but we were forced to move out of it so [the landlords] could cut it up and make smaller kitchenettes out of it." These units would house entire families that could range up to 10+ members.

Group of African American boys residing in Chicago, Illinois. Library of Congress

Restrictive covenants would envelope a wide array of areas within the city of Chicago. In an oral history interview, Earl Dickerson, a Chicago lawyer that challenged the legality of restrictive covenants in Hansberry v. Lee, discussed the broad presence that these covenants had in the city. With regards to both Chicago in general and Hyde Park, a neighborhood in the city, Dickerson stated the following: "When I was a boy in Hyde Park... [it] was not unlike much of the rest of the City of Chicago from the standpoint of race relations. Blacks could not live in Hyde Park... There were racial restrictive covenants in the Hyde Park area. There were racial restrictive covenants all over Chicago in those areas bordering the black communities." Dickerson would go on to discuss the covenant challenged in the Hansberry v. Lee case, stating that one covenant covering 26 city blocks was able to bar housing from all people of color.

African American woman standing in a deteriorated apartment in Chicago. University of Chicago Special Collections

Notably, these covenants were not just supported by property owners. Instead, a complex network of support from local and national professional organizations for realtors, local, state, and federal governments, the University of Chicago, and community organizations helped support restrictive covenants within Chicago. In the case of Hansberry v. Lee, Dickerson stated that the Hyde Park-Kenwood Improvement Association, a community organization made of members of the Hyde Park neighborhood, supported restrictive covenants in the area. This included filing lawsuits to evict African Americans who occupied covenanted housing.

From the widespread support and detrimental effects of restrictive covenants, the hopes of black migrants coming to Chicago would be significantly challenged. Those who sought an escape from the complex network of discrimination and white supremacy in the rural South would instead find a new web of white supremacy in Chicago and other areas of the North. This discrimination would not only impact the material conditions of African Americans, but their dreams for dignified living. On the issue of how restrictive covenants would be met by migrants, economist Robert Weaver wrote in 1948 that, "In our literature, folklore, and propaganda for free enterprise, we have glorified home ownership and desirable shelter. A decent and attractive home is one of the basic components in the American ideal of a high standard of living. Associated with this attitude, of course, is the traditional rural affection for land and the universal craving of farm people to own their home." Yet instead of living up to the American dream, Weaver wrote that African American housing was, "Full of accounts of vice, adult and juvenile delinquency, poverty, bad health, social and family delinquency, and deteriorated housing."

Further reading: The Negro Ghetto by Robert Weaver

Truman Gibson Jr. - A Connection to Hansberry v Lee, James Burke, and Shelley v Kraemer.

By LaDale Winling

More than once, Truman Gibson, Jr., had ringside seats to history.

In June of 1937, Gibson scored front-row tickets to the heavyweight title bout between Joe Louis and Jim Braddock. His father, Truman, Sr., was an attorney for the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance company in Chicago and had gotten his son tickets to see the crowning of the first Black heavyweight champ since Jack Johnson more than 20 years before.

The bout was held in a ring set up on the field of Comiskey Park on the South Side, and the city’s Black elite were joined by Black business and civic leaders from around the country who traveled to Chicago to see the favored challenger, Louis, take on the unlikely champ, Braddock. Braddock’s story was later immortalized in the Hollywood film Cinderella Man, starring Russell Crowe. The champ knocked Louis down in the first round, offering a respectable defense to his title, but Louis ultimately prevailed with a knockout in the eighth round.

Comiskey Park was the site of the heavyweight championship bout between James Braddock and Joe Louis in June, 1937. Truman Gibson and his father had ringside seats to this fight.

Chicago would soon be the site of another battle freighted with racial significance. Truman Gibson was an attorney and one of the first Black law school graduates of the University of Chicago. He worked with civil rights attorney Earl Dickerson, the UofC’s first Black law school alumnus, who teamed up with Carl Hansberry and Harry Pace to make a legal challenge to racially restrictive covenants, a battle that would go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1940.

Gibson, Jr.’s role in the Hansberry case was to research the covenant’s paperwork – how many property owners signed, how much road frontage their land had, and what proportion of the necessary 95% of area frontage it actually covered. He had been tipped off by James Burke, the embittered former president of the Woodlawn Property Owners Association, that the association had not gathered enough signatures, and Gibson had to prove it. That research and documentation was the fulcrum of the court case in Hansberry v. Lee – it was the basis of the ruling making the South Side covenant inoperative. However, the court sidestepped the fundamental Constitutional question that the Hansberry lawyers raised about all covenants, which would have to wait nearly a decade for other legal challenges, which came together in the cases Shelley v. Kraemer.

Truman Gibson testifying before U.S. Senate committee, 1948

Truman Gibson’s role in covenants challenges was over, but his legal career was just beginning. Gibson met Joe Louis while the boxer was in Chicago, and the two became friendly. After the champ ran up debt during World War II at the hands of his promoter, Gibson became Louis’s manager. As Louis’s fighting abilities deteriorated, Gibson helped found the International Boxing Club in order to crown a successor to the aging heavyweight champ. Louis retired in 1949 and the IBC created an elimination bracket among leading contenders to make a successor as heavyweight champion.

Mr. Truman K. Gibson, Jr., Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, pictured at press conference Monday, April 9, following his return from Mediterranean and European Theaters of Operations, 04/09/1945 – Public Domain (Wikipedia)

During the war, the Roosevelt administration enlisted Gibson as a racial advisor for the military during World War II. Gibson advised Secretary of War Harry Stimson, helping address problems of discrimination and issues of inequality and mistreatment arising from segregation in the military, such as advocating for more Black officers and supporting their rise through the ranks. In that role, Gibson played a hand in creating the WWII propaganda film, The Negro Soldier, directed by Frank Capra, which positively portrayed the fighting capabilities and the contributions of African Americans.

Truman Gibson lived in metro Chicago and practiced law until his death in 2005. He published his memoir Knocking Down Barriers: My Fight for Black America that same year.

Bernard Sheil, World War II, and Restrictive Covenants

By Raaj Aggarwal

Black Chicagoans battling against housing segregation found an ally in the interracial fight against covenants. Bernard Sheil, a white Catholic bishop, would play an influential role in ending restrictive covenants and other forms racial segregation. Historian Timothy Neary in Crossing Parish Boundaries: Race, Sports, and Catholic Youth in Chicago, 1914-1954 writes that Sheil lived a life that, “Developed a Catholic [vision] of American pluralism that included African Americans.” As such, Sheil would help combat racial injustice during the 1930s, World War II, and the postwar period. This would include joining African Americans in helping to end restrictive covenants.

Over one million African Americans fought in a segregated military during World War II to fight fascism abroad, only to return to racial oppression at home. In observance with this reality, Bernard Sheil, a bishop of Chicago, firmly declared that as African Americans, “Ceased to die in the muddy fields of Germany and on the coral beaches of the South Pacific… the anti-poll tax bill was allowed to languish and die in the Congressional hopper.” He’d further lament that, “Young colored Americans no longer had the opportunity to prove their love for their country by winning decorations for gallantry and bravery. [Yet those] who continued to plead for the establishment of a fair employment practices act [and] begged that colored Americans be given an opportunity to cast their ballot found themselves stigmatized as 'crack-pots'... This was the shocking answer of white America to the plea for racial justice.” This decry was part of an address titled "Restrictive Covenants vs. Brotherhood" given in 1946 to the Chicago Council Against Racial Discrimination less than a year after the end of World War II, with the goal of condemning the residential segregation caused by restrictive covenants.

Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, Deputy Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean Theater, inspects Honor Guard of MPs during his tour of the Fifth Army front at the 92nd Division Sector. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/531415

Up to this point, Sheil was known to be a champion for racial justice, especially as a man of Catholic faith. Born in Chicago as a second-generation Irish American in 1886, Sheil would assume the prominent position of auxiliary bishop in 1928. Thanks to his charismatic leadership, Sheil would go on to found the Catholic Youth Organization in 1930 during the calamity of the Great Depression, which leveraged Chicago’s local community assets to provide sports activities to Chicago's youth for boys and girls, regardless of race. Notably, Sheil’s organization differed from the YMCA and other organizations due to there being no racial segregation within the CYO during this time. Sheil would also support the African American community within Chicago in many other ways, such as opening a community center in the heart of Chicago's Black Belt. Before and during this time, Sheil would be a national champion not just for racial equality, but would also speak across the country on causes ranging from supporting Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal programs to denouncing anti-semitism during the lead up to World War II.

Bishop Bernard Sheil and boxers in a 1950 promotional shot for Catholic Youth Organization boxing championships (Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center)

Sheil felt the need to attack residential segregation after World War II due to the immense challenges in housing that African Americans faced across the country. Housing construction and repairs slowed down during the Great Depression. This would continue to further stall during World War II as the nation concentrated its labor and industry towards the war effort. As such, the country was engulfed in an immense housing shortage during the immediate postwar years. This issue was further compounded for African Americans, who faced this general shortage in addition to the myriad instruments of residential segregation that would cause further obstacles to housing, with racially restrictive covenants being one key factor.

Sheil vilified racial covenants in his address. They forced African Americans into overcrowded homes in disrepair, further enabling communicable diseases to spread within overcrowded residential complexes and communities. Restrictive covenants furthermore helped to cement widespread beliefs that African Americans could not live harmoniously with white America. Dominant in the first half of the 20th century, Chicago would see a surge in covenant creation in the 1940s following the start of the Second Great Migration. As such, African American veterans returned from their courageous fight against fascism only to be welcomed by a reinvigorated, oppressive campaign of residential segregation in an already constrained housing market.

An African American boy living in a deteriorated home with impoverished coverings and boarded up doors. https://photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu/db.xqy?one=apf2-09370.xml

It was this hypocrisy that Sheil sought to attack, viewing that restrictive covenants had deleterious impacts that both involved and transcended the material conditions of African American livelihood. Sheil announced that some of the consequences of restrictive covenants included, “Poor health, improper housing, disease, and crime.” Yet he also viewed restrictive covenants as an issue that involved much more than physical standards of living. Instead, he saw the predicament of restrictive covenants as, "A problem that far transcends the question of democratic rights. It is one of the most basic factors mitigating against interracial harmony."

In addition to racial harmony, Sheil also viewed restrictive covenants as being contradictory to the Christine doctrine, stating that, "It is sickening to realize that… restrictive covenants and all of the other inhuman racial practices to which we have become inured are diametrically and blatantly opposed to every concept of Christian ethics." Sheil continued to discuss the hypocrisy he saw in Christians, declaring that those who silently accepted African Americans being forced into "legalistic concentration camps of America... drifted from the original command, 'Love One Another.'" As such, Sheil called on Christians to live with greater integrity in accordance with their own ethics, and to reevaluate who is to be included in the brotherhood of man.

Along these lines, Sheil denounced both the hypocrisy of Christians and the American public turning a blind eye to the oppression of African Americans, stating that the US was committing, "The very crimes of which we accused Nazi Germany." He proudly announced the valiant effort that African Americans had in the fight against the Axis powers and the strong hopes that champions of racial justice had for recognizing the humanity of African Americans. Yet Sheil also lamented that despite these aspirations, the hopes that “America would move confidently forward to the fulfillment of the age-old dream… boldly enunciated in the 'Land of the Free and Home of the Brave,'” would not be actualized. Instead, Sheil observed that America would continue to live within an outrageous double standard through allowing tyrannical oppression to thrive within its own borders. In his reaction to this intolerable hypocrisy, Sheil concluded his speech by stating that there, “Is never a time for compromising with fundamental moral principles. Either we believed and meant what we announced to the world concerning the dignity of man and the essential community of his nature, or it is a lie. If we meant it then let us, for the love of God, begin to practice it, honestly and objectively.”

Bishop Sheil poses with children and a large cake celebrating the 21st anniversary of CYO's founding on May 25, 1951. (Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center)

Sheil would go on to live his life in accordance with this integrity of Christian ethics, continuing to champion racial justice. After this address, Sheil worked with the Chicago mayor and labor leaders to improve race relations when postwar public housing for African Americans and racial integration began, among other actions. Following the Supreme Court’s 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer ruling that made the enforcement of restrictive covenants illegal, Sheil’s fervent passion for racial justice persevered as he would later lament that “The Negro has not received a square deal, an honest deal, or a new deal from white America.” As such, Sheil would continue to serve as the director of the Chicago Youth Organization until he stepped down in 1954. While Sheil passed away in 1969, his legacy is still remembered and studied by modern scholars, as his powerful story and genuine integrity can inform those seeking to more earnestly live in accordance with their values.

Further reading: Crossing Parish Boundaries: Race, Sports, and Catholic Youth in Chicago, 1914-1954 by Timothy Neary

Helen Monchow

By Maura Fennelly

In the preface to her book titled The Use of Deed Restrictions in Subdivision Development, economist Helen Monchow writes: “From the standpoint of controlling development the pattern of our modern cities is determined largely by the activities of two groups, the realtors and the city planners” (p. iii). While these two actors undoubtedly had significant power in constructing and controlling urban landscapes, Monchow left out another key group within the network of real estate to which she herself belonged: researchers.

Dr. Helen C. Monchow

As a White female economist, Helen Monchow was an exception to the otherwise White male-dominated network of people shaping real estate and land use in the early 20th century. Her research career was short due to her death at 52, but in three decades she contributed to racist segregation policies that protected White owners’ property values and destroyed minority neighborhoods through urban renewal.

Thanks to Monchow’s alma mater, Mount Holyoke College, there are detailed accounts of her academic and professional career roles. Born in 1898, she spent her early years in Ohio before moving to Massachusetts to attend the all-women’s college. She remained heavily involved with her alumni network until her passing, with her friends still calling her by her college nickname “Monox” long after graduation. She served as a Holyoke trustee with Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins by the late 1930s and was part of numerous women’s organizations like the Women’s College Board of Chicago and the American Advancement of University Women. She also contributed to a fund in her name that would pay for several students’ cost of attendance.

Monchow’s Responses to Mount Holyoke’s “Biographical Data for the College Press Bureau”, 1939

For two years (1920 to 1922) she worked as a record clerk in Cleveland, probably in an office similar to the one where we do our Chicago Covenants research sessions. She also had a stint at the Women’s City Club in Cleveland, an organization focused on promoting women’s engagement in civic affairs. She then moved to Chicago, where she worked as Richard Ely’s personal secretary. before enrolling in economics classes and eventually joining his Institute for Research in Land Economics. Ely is known as the “father of land economics'' and advanced racist ideas of land valuation that laid the groundwork for practices like redlining.

Note for Alumnae Record at Mount Holyoke College describing Monchow taking a secretary position with Richard Ely

Despite finding much success in academic research, Monchow expressed frustration over a lack of advancement due to her gender. All the while, she wrote one of the most influential pieces on land valuation before earning her PhD in 1937. In 1928, she published The Use of Deed Restrictions. In the book, Monchow analyzed the use of restrictions in subdivisions across the U.S. and argued that deed restrictions had advantages over zoning because of the granular property-by-property detail that could go into their restrictions.

In the book, Monchow examined 84 deeds and 40 of them contained race restrictions. The majority of the deeds with restrictions were newer, which suggests the growing popularity of covenants after the Corrigan v Buckley Supreme Court Case in 1926 that deemed racial covenants to be constitutional. Monchow was aware of the ambiguity of covenants’ legal standing, even with the Corrigan ruling. She knew government-issued racial restrictions were no longer permissible after the Buchanan v. Warley Supreme Court Case in 1917 that deemed a Louisville, KY segregation ordinance was an overreach of police powers. However, residents and developers still had power to use private contracts to restrict people on the basis of racial classification.

Real estate researchers and practitioners commended Monchows’ findings. JC Nichols, the first subdivider to use deed restrictions and who popularized the practice, wrote such an extensive positive review of Monchow’s book that it was turned into a stand-alone article in The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics. He wrote: “Few people realize the terrific economic waste, estimated at more than one billion dollars a year, of rapid changes in the character of residential neighborhoods in American cities. Stability, permanence, or, if you will, orderly progress, conceived and aided by city planning officials and by developers using deed restrictions, combat this waste.” Monchow’s study served as a manual for real estate developers to discriminate, under the cover of efficient land development.

Monchow continued to be a leading influence in academic and policy discussions surrounding real estate. She served as managing editor for the top land economics journal, The Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics of Chicago from 1931 and 1942. Richard Ely’s son-in-law and economist Edward Morehouse noted that during Monchow’s tenure as editor, “During the next 11 years, a period of uncertainty and real "Sturm und Drang" for the journal, Miss Monchow carried virtually single-handedly the responsibilities of editing the journal and securing the generous assistance of Northwestern University in continued publication.”

In addition to demanding journal management responsibilities, Monchow published a second book, Seventy Years of Real Estate Subdividing in the Region of Chicago, in 1939. The book identified peak subdivision cycles between 1891 and 1926, which coincided with population growth in the Chicago area. Homer Hoyt, the former Chief Land Economist of the Federal Housing Authority responsible for establishing racist FHA underwriting guidelines, was a fan of Monchow’s study. In a review of the book, he lauded her for its detail on development trends and noted that an excess of subdivision development contributed to blight on the fringe of cities. Hoyt argued: “the need for control of future subdividing is evident, and Miss Monchow's authoritative study is indispensable for legislators contemplating methods of regulation.” Such regulation includes restrictive zoning measures that are now commonly debated today due to their role in limiting the supply of housing.

Homer Hoyt is traditionally known for his work “pioneering work in land use planning, zoning, and real estate economics”. However, we now know Homer was also responsible for writing and establishing racist FHA guidelines.

Once earning her PhD, Monchow remained as a faculty member at Northwestern for a brief period and taught courses. She moved more directly into the policy field when she became a city planner with the Chicago Plan Commission in 1941. As she succeeded professionally, Monchow wrote about wanting to contribute to the war effort. She moved to Washington, D.C. to become the Editor of Publications for the National Housing Agency (NHA). There she was able to work on wartime and postwar policies for veteran housing and also volunteer with the Red Cross by preparing surgical dressings.

While supporting state-funded projects to support returning veterans, Monchow continued to contribute to racist housing policies. An obituary for Monchow discusses her role with the Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA), which preceded the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Monchow participated in writing Title 1 of the Housing Act of 1949, which has been described as funding slum clearance and urban renewal across the U.S. as cities then had the power to use eminent domain to deal with “blighted” areas. Her final role at HHFA was with the “Division of Slum Clearance and Urban Redevelopment”. Despite resident resistance, urban renewal projects led to the destruction of entire neighborhoods. Similar to racial covenants’ impacts, these projects most negatively impacted non-White residents who lived in undervalued and underinvested spaces.

In 1950, Monchow died unexpectedly after an operation due to complications from lung cancer. Yet in such a short period she became a key actor in a growing network of real estate stakeholders and institutions. Monchow was a pioneering woman in economics and especially land economics – her contributions to research on land economics and subdivision deed restrictions cannot be understated, where her work remains heavily cited by historians [and economists] to this day. Monchow’s commitment to supporting women in education served as a foil to the implications of her research.

Tovey v. Levy: Ending State Enforcement and Beginning Key Research

By Gabriel Bassin

On November 18, 1948, the Supreme Court of Illinois issued an important decision on enforcing racially restrictive covenants in Chicago. Just months beforehand, the U.S. Supreme Court radically reduced the power of restrictive covenants in Shelley v. Kraemer, determining that courts could not enforce these agreements. In some respects, Tovey v. Levy simply followed in the footsteps of the Shelley v. Kraemer decision, ruling in line with the higher court. But before the decision, this case did threaten the enforcement of restrictive covenants before the court reaffirmed the state’s inability to do so.

The most significant element of Tovey v. Levy may lie beyond the outcome of the case. Tovey v. Levy incorporated a unique research study that detailed the scope and impact of racially restrictive covenants in Chicago as evidence in its trial. In a way, it set a precedent for the future studies such as the Chicago Covenants Project in addition to serving as the basis for evidence used in later U.S. Supreme Court rulings. Thus, the story of Tovey v. Levy demonstrates both a historically critical restriction of states enforcing racially restrictive covenants and the necessary framework for future court rulings and research projects.

Highlighted area is 417 - 421 W. 60th St. in Englewood.

The case began with a restrictive covenant that included 417-421 W. 60th Street in Englewood. [1] Hyman L. Levy and Chritene J. Levy, the previous owners of the building, signed a racially restrictive covenant with their neighbors in 1928. [2] In 1944, the Levys executed a deed with the Cadillac Hotel Corporation, who immediately leased the property to Joseph J. Allen, a Black man. [3] Allen proceeded to lease/sublease different units on the property to a number of Black residents. [4] In response, the plaintiff, one of the neighbors party to the covenant, filed for an injunction on the grounds that this constituted a violation of the previously signed covenant. [5] Upon reaching trial, the defendants' lawyers, who worked for the NAACP, argued the covenant was invalid, taking issue with its constitutionality, its definition of Black people, various spelling errors, smudges, and deviations in the owners’ names. [6] In spite of their efforts, the trial court ultimately deemed the covenant valid and ruled for an eviction, which the Chief Justice of the Superior Court enforced shortly afterward by decree. [7] With this decision, an Illinois court threatened by decree to evict Black residents under the provisions of a covenant. The Supreme Court was on the cusp of breaking a major barrier, allowing Black people to move into previously restricted neighborhoods where owners were willing to lease their properties, without threat of eviction. Yet just ahead of this key decision, an Illinois trial court judge had reaffirmed the enforcement of restrictive covenants through state action.

At the time, lawyers with the NAACP had been strategizing to dismantle racially restrictive covenants, actively involved in previous covenant cases. In 1940, the United States Supreme Court decided Hansberry v. Lee, building hope that they could successfully challenge covenants and win. In 1942, Charles Hamilton Houston, an NAACP lawyer, then successfully argued Hundley v. Gorewitz. However, in 1945, when Mays v. Burgess was denied certiorari by the United States Supreme Court, NAACP lawyers gathered in Chicago to institute a new strategic approach. [8] During the trial, NAACP lawyers who were involved in the defense of Tovey v. Levy presented the case as a potential opportunity to reach and win in the Supreme Court. Loring Moore, one of the lawyers, presented their approach of employing sociological and economic expert testimony in conjunction with a research study in this case. [9] While Shelley v. Kraemer ended up being the case to reach the Supreme Court, Tovey v. Levy helped develop the key approach of introducing empirical research, thereby engaging sociological and economic evidence in the courtroom.

Loren Miller was an influential American journalist, civil rights activist, attorney, and judge. As chief counsel in 1948 he helped outlaw racial restrictive covenants in Shelley v. Kraemer.